Exploring text‑adventure games before graphics

Text‑adventure gaming represents the rawest form of digital storytelling, where the screen serves as a window into a world built entirely by your imagination.

Anúncios

Before the era of high-definition textures and ray tracing, players relied on “parsers” to communicate with virtual environments using only text commands.

The beauty of this medium lies in its ability to render infinite detail without a single pixel, challenging the player’s intellect rather than their reflexes.

Today, in 2026, we see a surprising revival of this “Interactive Fiction,” as modern gamers seek deep, narrative-driven experiences away from visual noise.

Inside the World of Words

- The Engine of Logic: How text parsers translate human intent into game actions.

- The Infinite Canvas: Why the absence of graphics allows for deeper environmental immersion.

- Pioneering Titles: A look at the classics like Zork and Colossal Cave Adventure.

- Modern Resonance: The influence of text logic on current AI-driven narrative games.

What is the appeal of gaming through words alone?

Playing a text‑adventure is akin to reading a book where the ink changes based on your every decision, making you the ultimate co-author.

This genre stripped away the limitations of early hardware, allowing developers to describe vast galaxies or intricate dungeons that no 1970s computer could draw.

Engagement comes from the direct link between the player’s vocabulary and the game’s reaction, fostering a unique sense of agency and discovery.

You aren’t just watching a character move; you are mentally inhabiting the space, feeling the cold stone of a dungeon or smelling the salt air.

Historically, these games required a high level of literacy and lateral thinking, often presenting puzzles that demanded real-world knowledge or careful observation.

Titles like The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy by Infocom turned the very act of understanding the narrative into a challenging, often hilarious, gameplay mechanic.

Even in 2026, the psychological impact of a well-written sentence often outweighs a cinematic cutscene, as the mind creates more vivid horrors and wonders.

This subjective rendering ensures that no two players ever see exactly the same world, even if they read the same words on screen.

++ Restoring audio in classic 8‑bit soundtrack archives

How does the parser system function?

The parser acts as a translator, taking simple verb-noun phrases like “GET LAMP” or “OPEN MAILBOX” and checking them against a pre-defined world state.

Early systems were quite rigid, but they eventually evolved to understand complex instructions, including adjectives and prepositions, making the interaction feel remarkably fluid.

Developers spent months mapping out every possible action a player might try, creating “fail states” that were often as entertaining as the successes.

This logic-based framework laid the foundation for the branching dialogues we see in modern RPGs, proving that words remain the strongest building blocks for choice.

Also read: The legacy of Pong in contemporary indie scene

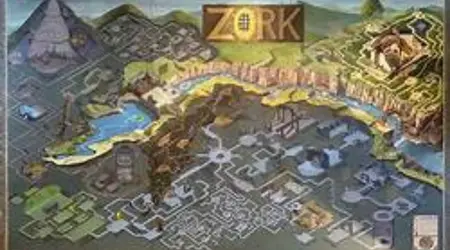

Why is Zork still relevant today?

Zork remains the gold standard of the text‑adventure genre because of its witty writing and the sheer depth of its subterranean world.

It proved that a game could have a personality, taunting the player or rewarding curiosity with dry, intellectual humor that became legendary among gamers.

By 2025, retrospective data from gaming archives shows that Zork remains one of the most accessed non-graphical titles in university computer labs.

Its enduring popularity stems from a design that respects the player’s intelligence, offering a timeless challenge that requires no hardware upgrades to enjoy.

Why did these games dominate the early industry?

Early computers lacked the processing power to handle real-time graphics, making text the only viable medium for complex, long-form digital entertainment.

Developers focused their energy on world-building and narrative branching, creating experiences like Colossal Cave Adventure that felt truly alive despite being made of letters.

The text‑adventure was the primary vehicle for virtual escapism during the mainframe era, allowing students and engineers to explore fantasy realms after hours.

It was a democratization of adventure, where a simple terminal could transport you to the ruins of a lost civilization or the bridge of a starship.

Research by the Digital Antiquary suggests that at its peak, the company Infocom held a significant share of the home software market.

Their success was built on “feelies” physical items included in the box, like maps or tokens, that bridged the gap between the screen and reality.

Can we truly say that modern photorealistic games offer more “immersion” than a game that exists entirely within the theater of your mind?

While graphics provide a specific aesthetic, the text‑adventure provides a spiritual depth, forcing the player to be an active participant in the creative process.

Read more: Building your own FPGA retro console

How did Infocom change the market?

Infocom elevated the genre by hiring professional writers and developing the Z-Machine, a virtual machine that allowed their games to run on any computer.

This technical foresight meant that a text‑adventure like Planetfall looked and played exactly the same on a Commodore 64 as it did on an Apple II.

Their commitment to high-quality prose transformed games from simple toys into a respected form of literature, paving the way for the “narrative” games of today.

This legacy lives on in 2026 through independent authors who continue to release free Interactive Fiction that pushes the boundaries of the form.

What are “feelies” and why do they matter?

“Feelies” were physical artifacts like the “Peril Sensitive Sunglasses” from Hitchhiker’s Guide or secret letters that provided clues for the digital puzzles.

These items turned the purchase into a collectible experience, adding a layer of physical reality to the text-based world on the monitor.

They served as a clever form of copy protection while deepening the player’s connection to the story, making the world feel tangible beyond the screen.

This tactile approach to world-building is something many modern digital-only releases still struggle to replicate with the same charm and effectiveness.

What is the legacy of text-based logic?

Modern gaming owes its structural soul to the text‑adventure, especially regarding how we handle player choice and non-linear storytelling in open worlds.

The “If/Then” logic used to check if a player had the brass lantern in Zork is the direct ancestor of the complex quest flags in The Witcher 3.

We see a full circle in 2026, where AI-driven “dungeon masters” are now generating dynamic text-based stories that react to virtually any input a player provides.

This technology is essentially a hyper-advanced parser, proving that the desire to “talk” to a machine and have it tell us a story is a permanent part of human-computer interaction.

Comparison of Defining Early Adventures

| Game Title | Year | Key Innovation | Narrative Tone |

| Colossal Cave | 1976 | First Parser | Exploratory / Naturalistic |

| Zork I | 1980 | Advanced Parser | Witty / Fantasy Satire |

| The Hobbit | 1982 | Real-time events | Epic / Tolkienesque |

| A Mind Forever Voyaging | 1985 | Social Commentary | Philosophical / Sci-Fi |

| Trinity | 1986 | Historical Fiction | Serious / Literary |

The text‑adventure is far from a relic; it is a fundamental pillar of interactive art that continues to influence how we tell stories in 2026.

These games proved that the most powerful graphics card in existence is the human brain, capable of rendering endless horizons from a single line of well-crafted prose.

By stripping away the visual, they forced us to listen to the narrative heart of the machine, creating a bond between player and programmer that is rare in today’s blockbuster era.

Whether you are avoiding a Grue in the dark or exploring a distant planet, the weight of your words remains the ultimate key to freedom.

As we move further into a future of virtual reality, perhaps we should look back at the quiet simplicity of the text terminal to remember what truly makes a story worth living.

Share your experience with your first encounter with a parser in the comments!

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a “Grue” in the context of these games?

A Grue is a fictional predatory monster from Zork that inhabits dark places; it became a legendary gaming meme because it would instantly kill players who entered darkness without a light source.

Do people still make these games today?

Yes, a vibrant community of authors uses tools like Inform 7 and Twine to create “Interactive Fiction,” which is the modern evolution of the classic text‑adventure.

What was the first text-based game ever made?

Colossal Cave Adventure, created by Will Crowther in 1976 and expanded by Don Woods, is widely considered the first true game of this genre.

How do I play these old games on a modern computer?

You can use “interpreters” like Frotz or Gargoyle, which are designed to run the original game files from the 80s on modern operating systems like Windows 11 or macOS.

Why did graphics eventually kill the genre?

As hardware improved, the mass market preferred the immediate visceral feedback of images over the slow, cerebral process of reading, leading to the rise of Point-and-Click adventures.